Everything you need to know about drum notes and drum score, collected in a handy drum notation guide

On your journey to becoming a better drummer, learning how to read and write drum sheet music is incredibly important. In fact, clearly understanding this language of drumming is a superpower.

Drum sheet music allows drummers to play new drum beats and perform songs without hearing or practising them beforehand. Drum music is made up of the percussion clef, drum notes, drum keys, crotchets, time signatures, quavers, semiquavers, drum fills, and bars, all precisely placed on the staff.

Though the ability to play music without ever hearing it may seem almost magical, once you understand the notes of drum sheet music, you’ll unlock this ability too.

In the same way that there are myths about how hard it is to learn drums, the idea of reading sheet music feels way outside the comfort zone of many drummers.

I wrote this drum notation guide to prove that it’s really not that difficult…

Reading drum sheet music is a great skill to assist you with your drumming even when you are first starting out playing, even if you’re learning without a drum set.

Gaining an understanding of how drumming patterns work before you take them to the drum set will give you a leg up and make it easier to understand and learn to play drum music that you love.

We recommend reading from the start of this drum notation guide to get the most benefit as each section helps you to understand the next more clearly.

However, you are welcome to use the links below to take you to each section individually if you’re returning to this guide.

How to read and write drum sheet music

- Learn the modern way to read drum sheet music

- Try out drum notation software

- Place your notes on the staff

- Choose the correct clef

- Remember the drum key

- Read your first drum beat

- Understand note lengths and note values

- Recognise crotchets

- Include a time signature

- Divide your music into bars

- Write drum score using crotchets

- Distinguish quavers from crotchets

- Use semiquavers to add variety

- Develop your reading ability to include drum fills

- Bring it all together by writing with crotchets, quavers and semiquavers

- Add rests to create space in your drum sheet music

- Discover our top tips for improving your reading

How to read drum music (the modern way)

Back in the day, learning to read music was, to put it simply, exceptionally dull.

No-one wants to sit around writing out squiggles that feel completely detached from the music that they love to play.

Thankfully, things have moved on a lot in the music reading world and learning this skill is way more creative, fun and easy-to-learn than it used to be.

So what’s different?

The old system involved taking drum lessons with endless books of music theory and drawing out different notes with pen and paper.

But now, sheet music apps and technology allows us to get instant feedback on what our sheet music sounds like.

When learning music in your drum lessons, once you’d drawn out or copied notes, you wouldn’t really have any idea what they sounded like.

You’d have to ask a teacher to play or sing it for you.

Now we have our very own personal teacher, available 24/7.

This new teacher is drum music notation software.

Drum music notation software

I know you’re ready to get started learning drum sheet music and I promise it’s on its way!

In my experience, one of the best ways to get the hang of reading music quickly is to get a free trial of some drum music software (PC or Mac only).

You’ll still benefit hugely from reading this guide without using this tool, but my experience is that you’ll have more fun if you do!

So why do I recommend this?

The software allows you to write out an idea in drum sheet music and then hear it back instantly.

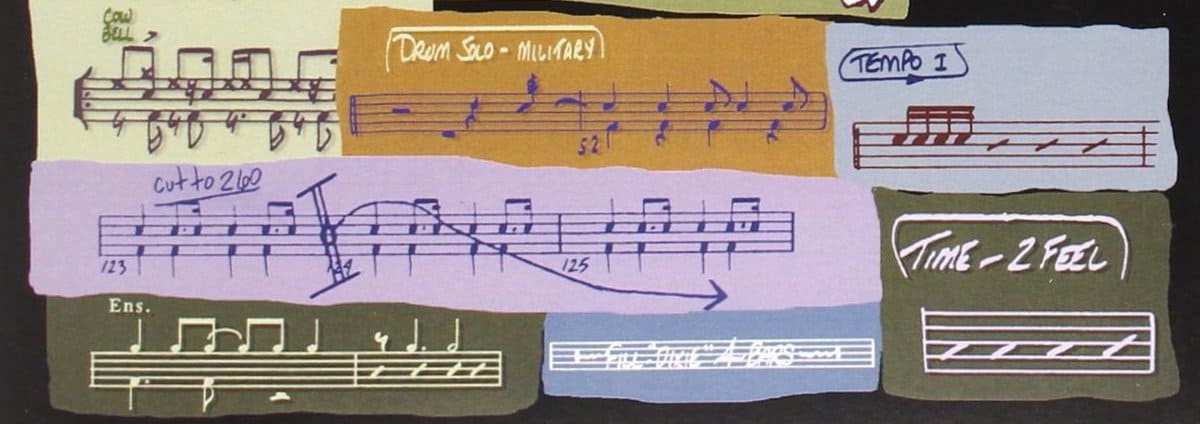

Here’s a beat I wrote out earlier:

You can check in to see if you made any mistakes, and it really speeds up your learning curve.

This allows you to create a really strong mental link between the notes you see on the paper, and the music you make on the drums.

Which drum music notation software should I try out?

After a lot of experimentation, I’d personally recommend you get a free trial of Guitar Pro.

As you’ll probably have guessed, Guitar Pro doesn’t just do drum music, but it’s by far the simplest software I’ve ever used for drum notation.

It’s super easy to pick up and you’ll be expressing your creativity in no time.

So, without further ado, let’s learn to read drum music notation!

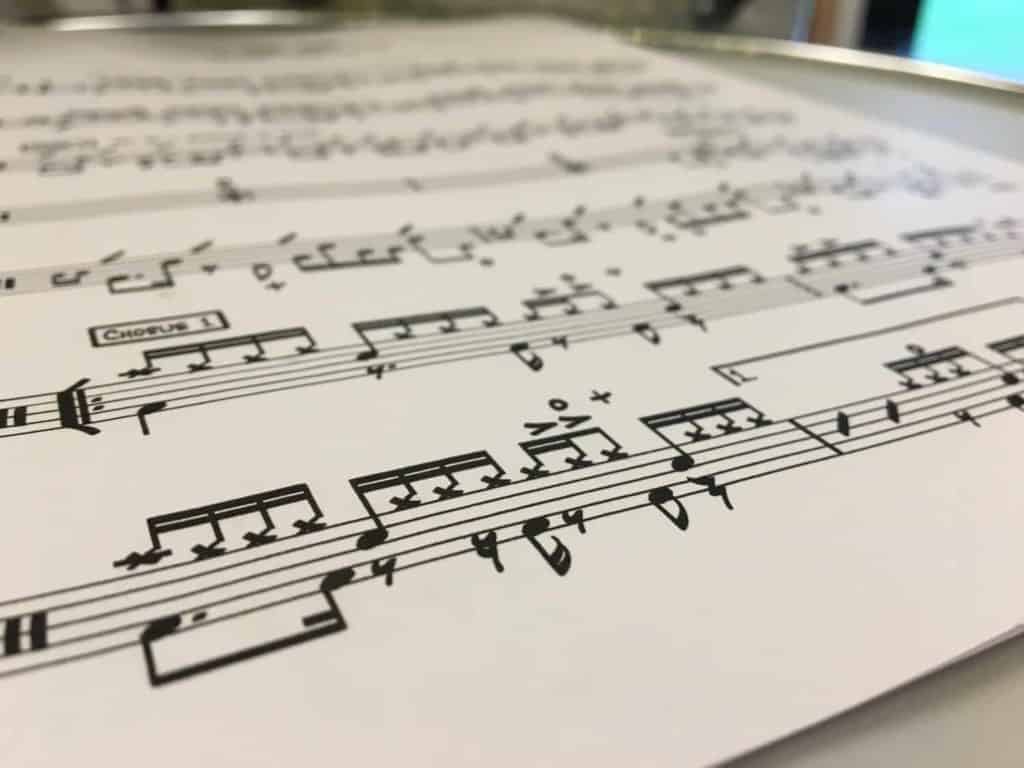

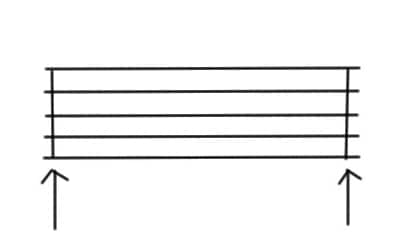

The staff

Before we get into the nitty-gritty of drum notes and notation, we first have to build the scaffolding that our drum notes will sit on.

We will be placing all of our drumming ideas onto five lines known as the staff (pronounced ‘stave’, like the word ‘rave’).

On the five lines, and in the spaces between them, is where we shall place our notes.

These lines neatly break up our notes and avoid the whole thing turning into an unreadable mess.

We want to be able to read through our music quickly and easily while playing a song, which is what makes the staff so important.

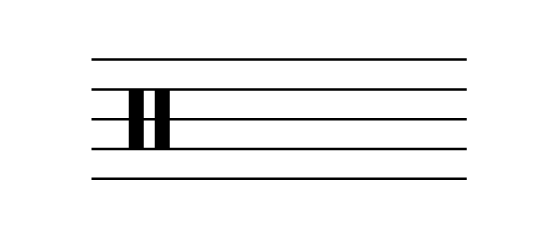

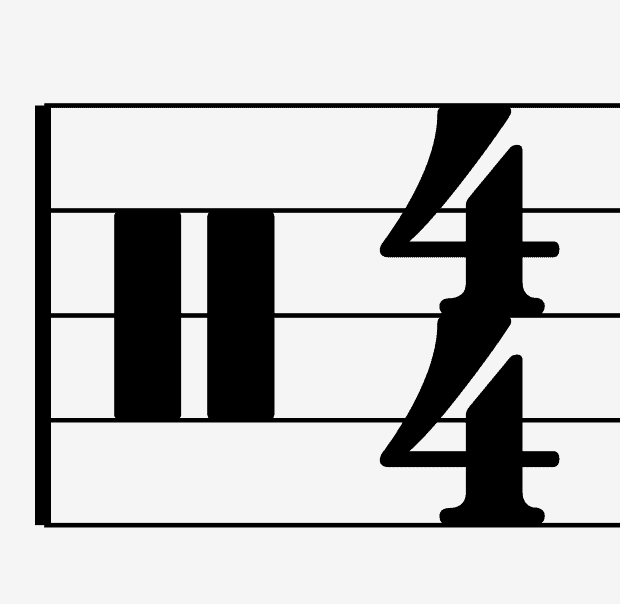

The drum clef

The problem is that all kinds of different musicians use the staff.

So how do we know that what we’re reading is drum sheet music?

Let’s face it, we’re going to look a bit silly trying to drum our way through a bassoon solo or a Spanish guitar melody if that’s what the sheet music was intended for.

Fortunately, us drummers have banded together and come up with a symbol of our own that you’ll see at the start of most drum music.

This tells you categorically that what you’re reading is designed for the drums.

This symbol is called the drum clef, or percussion clef.

If I’m being totally honest, we probably could have chosen a better one, because that symbol looks suspiciously like a pause button.

Confusingly, straight after you see that pause button, get ready to play!

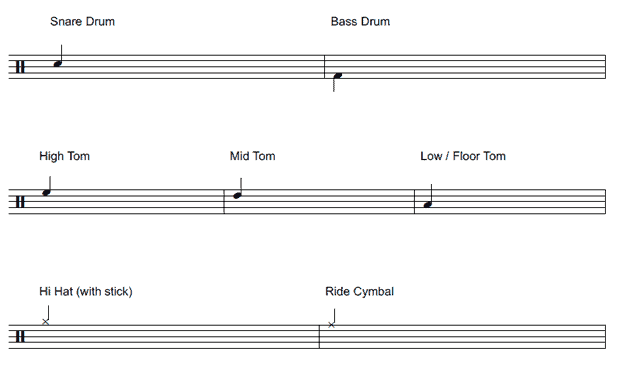

How to tell drum notes apart – the drum key

It’s time to start whacking some notes onto our staff.

But we can’t be throwing them around all willy-nilly.

It’s crucial to know – every drum has its own special place on the staff.

If you don’t put the note on the right line or in the right space, drummers will play something entirely different to what you intended.

Then your epic drum solo will instead sound like your drum kit falling down some stairs.

To avoid this potential catastrophe, we need to learn the drum key.

A drum key simply shows you which line or space of the staff represents a particular drum or cymbal.

Different keys are mostly the same, with small variations depending on the publisher of the music.

For example, different drum keys will contain different variations of the crash cymbal.

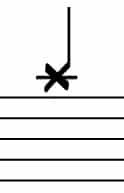

In most music scores, the crash cymbal looks like this:

But it could also look like this (or any other number of small variations):

When writing drum sheet music, you’ll typically use a cross to represent a cymbal, and a black circle to represent a drum.

As you get towards the more exotic end of cymbals, drums and drum techniques, these markings become a bit more flowery and exciting, but that’s a discussion for another day.

You don’t have to learn all of the drums and cymbals on the drum key now, but just know that these are the notes that turn up most often in drum sheet music.

Reading your first drum beat

It’s finally time to plot out and read your first drum beat!

To write out this beat, we have to understand one final piece of drum music theory.

Note lengths and note values

A note’s length/value tells you how long that note lasts in the music.

If you’re playing a slow old blues track, you’re likely to have big old note values with lots of time taken up by each note.

As a result, the music feels slow and relaxed. Everyone is taking their time with each note.

If you’re into heavy metal, and you’re playing thunderous double bass with both feet, the note values are likely to be a lot smaller, with lots of them squeezed together.

This makes the music feel fast and frenzied. These are the kind of notes you’d be likely to play in a drum solo too.

DID YOU KNOW? Frank Zappa famously wrote a piece called ‘The Black Page’. It was filled with so many small note values, pressed so close together, that the page appeared to turn almost completely black with ink.

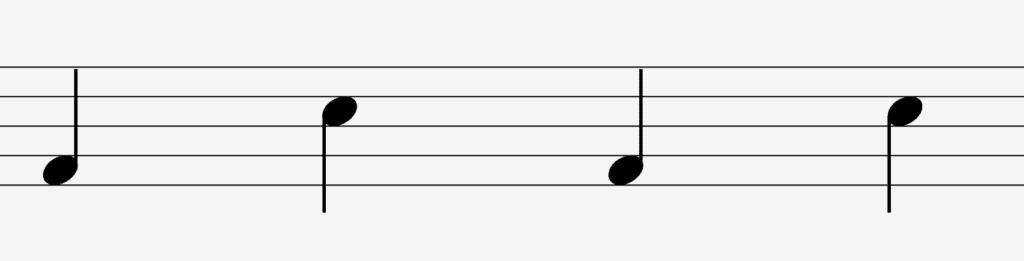

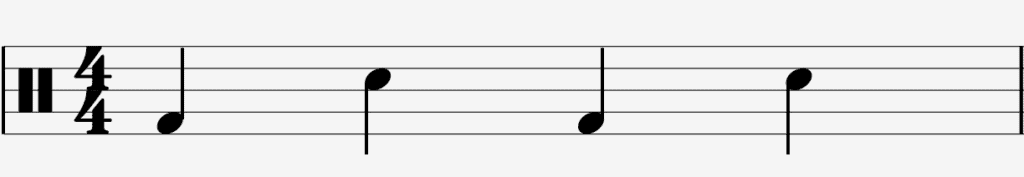

Starting it all off with the crotchet

The easiest note value to get the hang of is the crotchet.

Quite simply, a crotchet represents one beat of music.

When a drummer (perhaps you’ve done it yourself) shouts at the start of a song ‘1, 2, 3, 4!’, they are paying homage to the humble crotchet.

All they are doing is counting out 4 crotchets to kick the song off (known as a count-in), setting the speed at which the band will play.

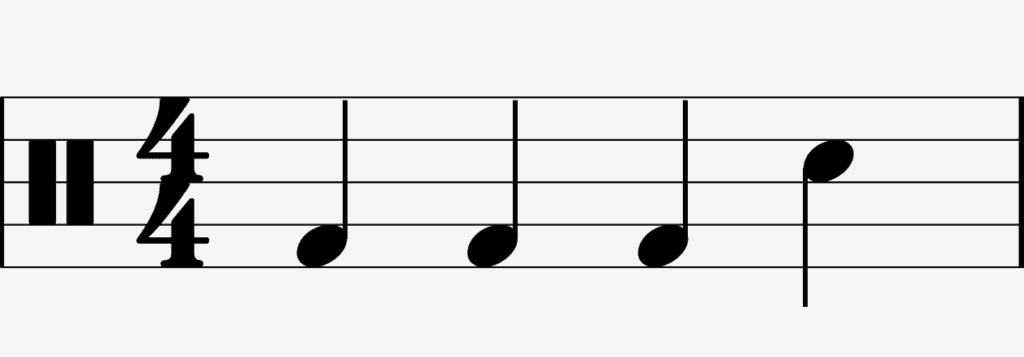

Have a look at some crotchets in action with our first drum beat example laid out in sheet music.

Here’s how it sounds as you’re having a look at the music.

HELPFUL TO KNOW: In all the audio clips in this guide, there is a count-in of 4 clicks. After that, the drum beat repeats four times, which makes it easier to press play and have a look at the music at the same time.

If you’re reading this on mobile, choose the ‘listen in browser’ option when listening to the beats to make it easier to follow along with the article.

You see how every note has that long stick either pointing up or down?

That long stick means the note is a crotchet!

Anytime you see that golf club stick poking up or down anywhere, think crotchet.

A bit further on down the tracks, we’ll look at ways you can add decorations to the golf sticks to change the value of the notes, but that’s not important right now.

In the example above, I’ve written a bass drum crotchet, followed by a snare drum crotchet, followed by another bass drum crotchet, followed by a snare drum crotchet.

If you wanted to, you could count ‘1,2,3,4’ over this, with one and three being the bass drums and 2 and 4 being the snare drums.

In fact, this pattern is the foundation behind many of the different drum grooves that we play.

Can you hear this crotchet rhythm of bass and snare in any of your favourite songs?

My personal favourite example is ‘Billie Jean’ by Michael Jackson. If you have a favourite song that features this common beat, let us know in the comments!

TIP: Don’t worry about whether the stick/golf club of the crotchet is pointing up or down, it doesn’t matter. We just put them one way or the other so that they are easier to read.

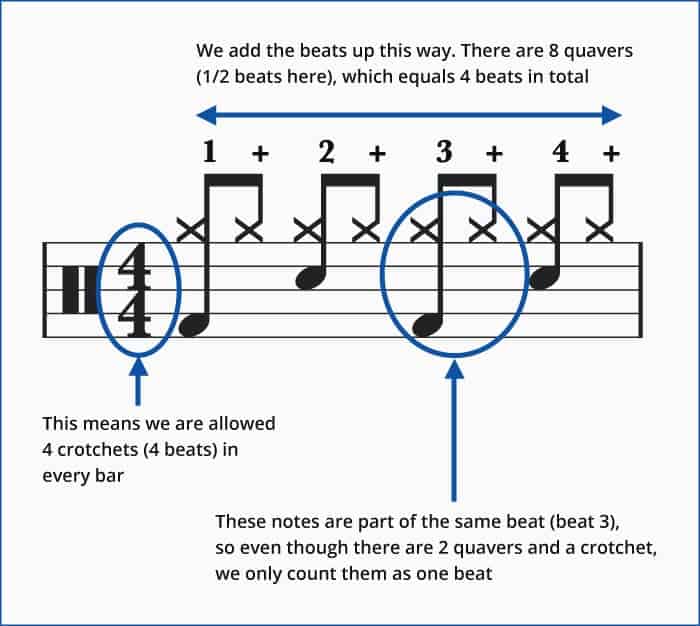

What is a time signature?

As musicians, we love putting things in fours.

The animals came in two by two but the musicians come in 4x4s (well, the successful ones do anyway).

In music, we can’t just have an endless line of notes going on forever and ever.

We need a structure, a little signpost to tell us how to feel the music rather than just play it.

The time signature breaks up the music into neat little chunks.

It gives us a better idea of how the music should flow, what notes we should emphasise and provides us with a framework for knowing where we are in the song.

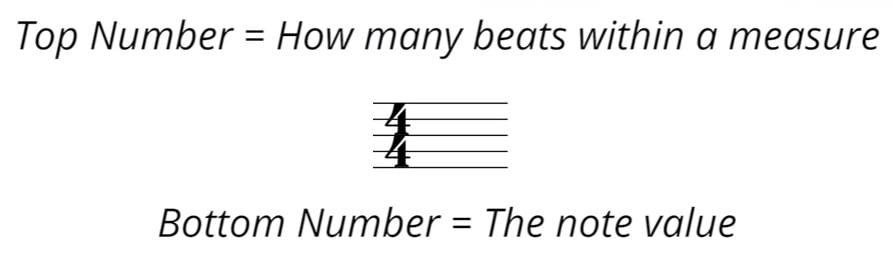

4/4 is the most common time signature and is written on the staff like this:

So what does 4/4 actually mean?

The number on the top of the time signature is the number of beats. In this case it’s 4.

The number on the bottom is the note value, which you may remember we looked at earlier. If you see a 4 here, that means you’re dealing with, you guessed it, the good old crotchet!

The time signature gives you a certain allowance of notes you’re allowed per chunk of music.

Think of it like spending money.

In this example, you are only allowed 4 crotchets worth of notes before your allowance runs out.

At that point, we stick a line down the staff to signify that this little chunk of music is done and there is no more room in this section.

Understanding bars

This little chunk is known as a bar, and the line down the staff is known as a bar line.

As soon as we’ve finished one bar, we can start another one, with the same rules as last time.

Bars are essential to make music easy to read and follow.

If I ever lose my place in the music, I can use the bar lines to quickly navigate around the page.

But it doesn’t stop there…

When you put a group of bars together, it’s typically known as a section (often labelled with A and B, or Verse and Chorus)

So in a song, you could have a verse section of 16 bars and then a chorus section of 16 bars.

Repeat that a few times and you have an entire song.

It all starts with the crotchet. Don’t underestimate it!

If you have any questions at all, do let me know in the comments section below.

Creative crotcheting – writing and reading your own personal drum score

Although I’m pretty sure crotcheting hasn’t yet made it into the dictionary, it’s the perfect description of our first creative exercise.

It’s time to put what you’ve learned to the test as you make your own drum beat using just crotchets.

Here are the rules:

- The music has to be in 4/4.

- You can only use the bass drum and snare drum.

- All the notes have to be crotchets.

So do you remember the drumbeat we looked at a little earlier on?

It looked like this:

And sounded like this:

This is far from the only way that we can arrange the bass drum and snare drum.

They don’t have to come one after the other, for example.

What if I put three bass drums in a row and then a snare drum?

That would look and sound like this:

Or what if I reversed the snare and bass drums to create something very different from what we’re used to hearing?

You can see how there are many possibilities, even with this strict set of rules.

Either on Guitar Pro, or on a sheet of paper, write out 2 of your own drum beat ideas using the template I’ve given you.

If you’re on Guitar Pro, have a listen back to them right away.

If you’re writing them on paper, try and imagine what they would sound like using the examples above as a reference.

And if you’re feeling really snazzy…

Why not do a beat that has multiple bars and changes the drum beat in each bar?

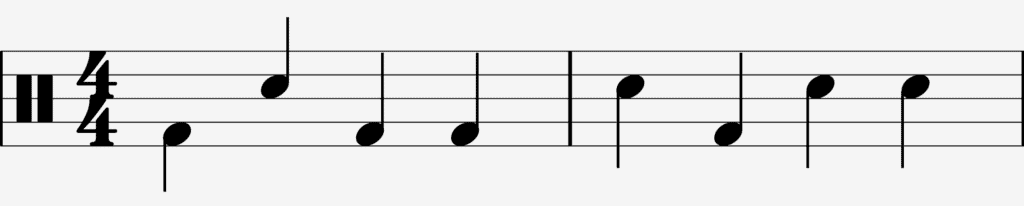

Here’s one I made earlier:

Once you get rolling, it’s easy to get your creativity flowing and start to use drum notes and notation as a way of creating new ideas that you can then take to the drum kit in real life.

The better you get with scoring drums (the fancy word for writing sheet music), the more intricate, exciting and awesome drum beats you’ll be able to create.

Introducing quavers

Variety is the spice of life, and even if your crotchet beats are the talk of the town, you’re going to want to take things to the next level soon enough.

The quaver (aside from being a delicious crisp) is the next note value on our odyssey through sheet music.

It is worth ½ a beat, meaning that in every beat of music, you’ll get 2 quavers.

Pretty straightforward, right?

Decorate your golf clubs

Remember earlier how we talked about the long stick of the crotchet?

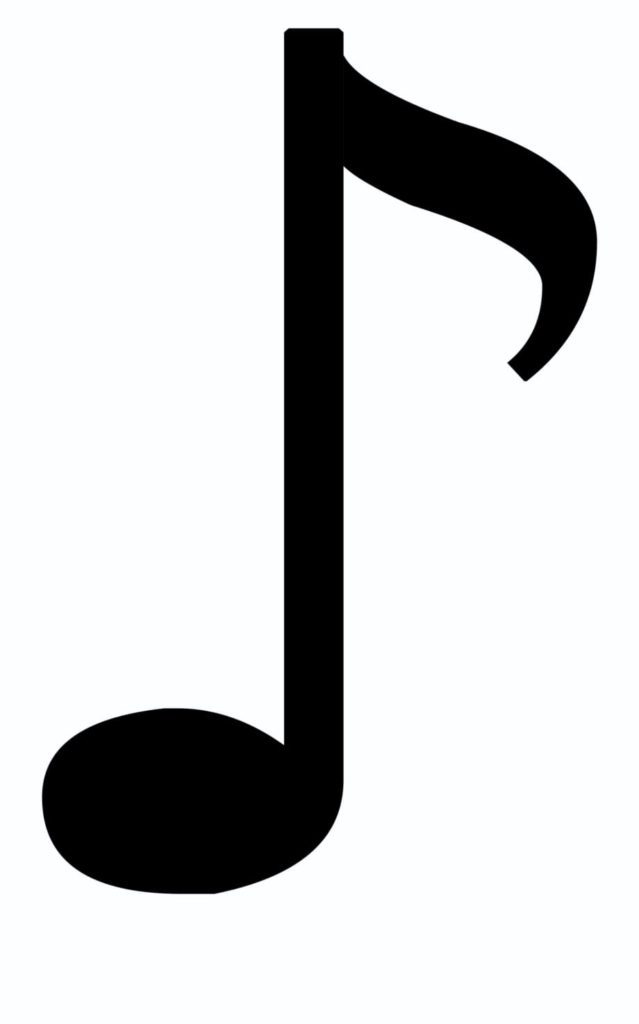

Well to make it into a quaver, all you have to do is stick a little flick on the end, like so:

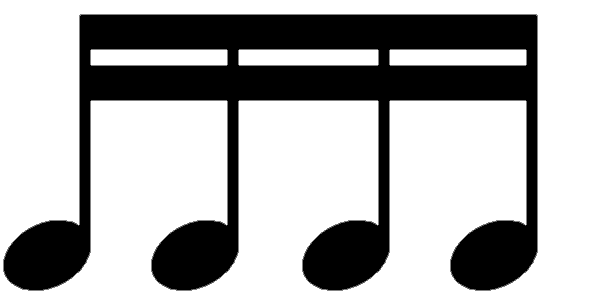

If you have two quavers in the same beat, you join them together in a little bridge, like this:

You’ll most commonly find quavers hanging out on the hi-hat line of drum sheet music, but they also add great variety to snare and bass rhythms.

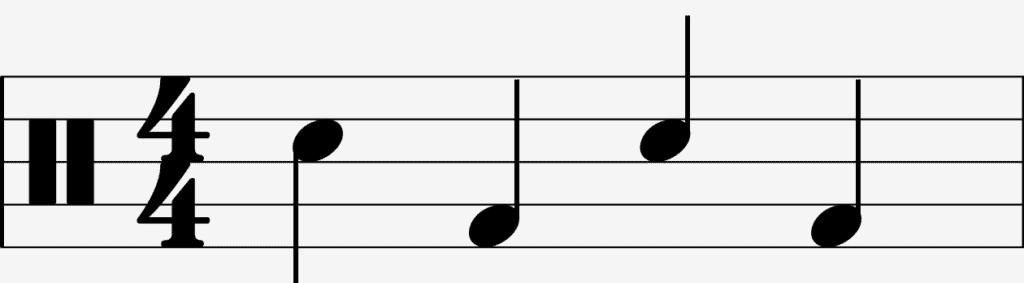

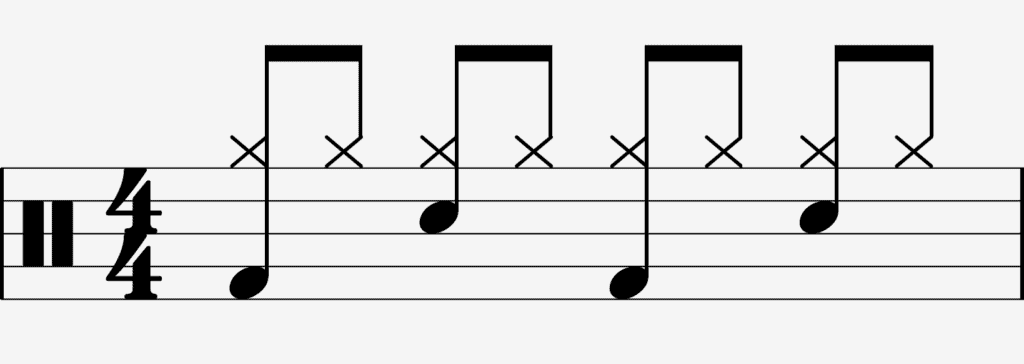

The most classic use of quavers you’ll see in a drum beat is above the bass snare bass snare crotchet pattern that we explored earlier.

Here’s what it looks and sounds like:

Unleashing the quavers

As the quavers are twice as fast as the crotchets, we count them slightly differently.

Rather than using ‘1,2,3,4’, we use ‘1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and’.

Do you see how we’re bringing the two concepts of quavers and crotchets together?

The quavers are ticking along at the top (1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and)

The crotchets are marking the beats below (1 2 3 4)

This drum beat is unbelievably popular, and almost every drummer will have been exposed to it.

This is the first time we’ve seen two notes happening at the same time on our sheet music, so before our brains explode, let’s clear up exactly how that works.

Whenever you see two notes that line up vertically on sheet music, you play them at the same time.

If you have notes that line up vertically, then they happen on the same beat.

People often get confused because it looks like you have more than four beats in the bar, because if you add all the notes up in the example above, you end up with 8 beats worth of notes.

But actually, our ‘allowance’ of beats (see time signature section) is only measured sideways, not vertically.

This allows us to play lots of different drums at the same time, while still dividing our music into little chunks using our time signature.

If you’re struggling with this, don’t panic! Have a re-read of the time signature section and let us know if you have any questions.

Now let your imagination run wild

You now know how to read drum sheet music with both crotchets and quavers.

This means you can design your own drum beat with both in mind.

Jump onto Guitar Pro or grab a pen and paper and see what you can come up with.

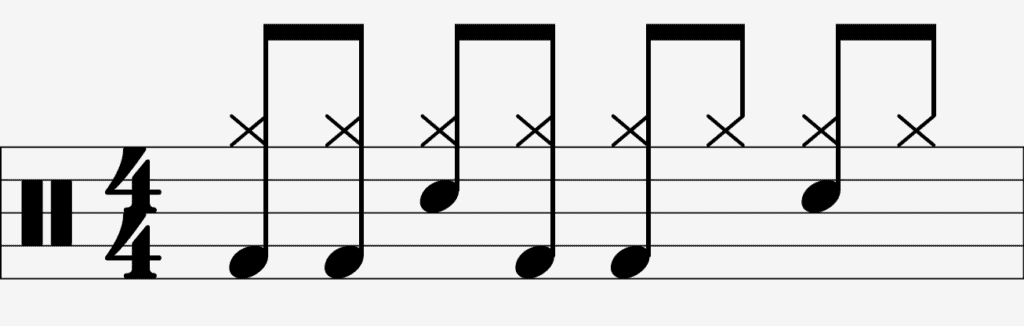

You could keep the general look of the above beat and turn the bass drums into quavers, like this:

And you could space the hi-hats out using crotchets, like this:

Any combination of crotchets and quavers, hi-hats, snare and bass will create a fantastic new beat.

You can then take those beats to the drum kit and bring them into reality.

Bring on the semiquavers

Semiquavers are the powerhouses of the drumming world. They are the final note value that we’re looking at in this guide.

If want to learn drumming patterns that are going to wow your audience, you better make sure you’ve got some semiquaver fills in your arsenal.

That’s just one of the reasons why it’s so useful to be able to read drum sheet music containing semiquavers.

While it’s not uncommon to put semiquavers into drum beats, you’ll most likely hear them at the end of sections in the form of a drum fill.

So if a crotchet is worth a beat of music and a quaver is worth ½ a beat, how much do you think a semiquaver is worth?

If you said a ¼ a beat, you’re killing this.

There are four semiquavers per beat. We use two flicks on the long stick of a crotchet to turn it into a semiquaver, which looks like this:

When there is more than one semiquaver in a beat, we join them together in a bridge like this:

Can you see how the same sort of rules and logic that we used for crotchets and quavers also applies to semiquavers?

It’s really useful to be using something like Guitar Pro to be able to hear different semiquaver combinations in action.

Semiquavers can be a little difficult to ‘hear in your head’ if you’re not used to writing them out regularly.

Instead of counting ‘1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and’ like we did with the quavers, we count semiquavers like this:

‘1 e and a 2 e and a 3 e and a 4 e and a’

If that makes your head spin, try the phrase ‘coca cola’ instead.

The name splits nicely into four syllables which sound like semiquavers when you say the word out loud.

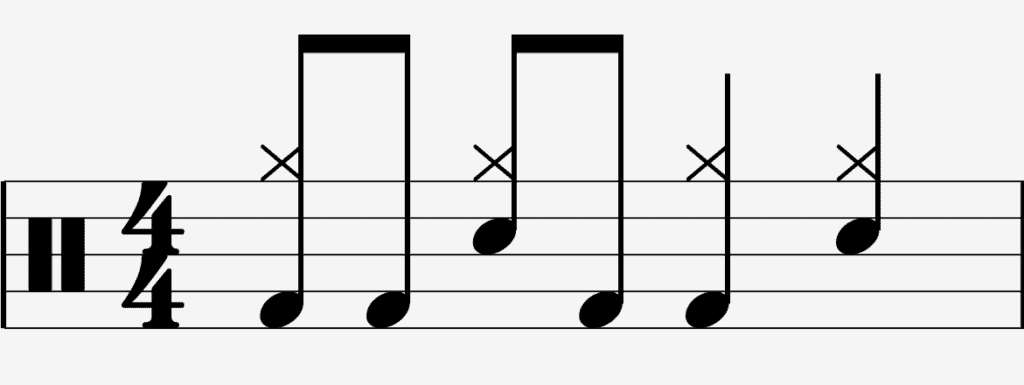

How to read drum fills

Let’s show you a few examples of semiquaver drum fills in sheet music.

Because we typically play a drum beat before a drum fill, I’ve put both together so that you can see them in context.

Example 1

In example 1, we use 4 semiquavers on the snare drum to fill in the last beat of the last bar.

This creates a cool variation to our standard beat which can grab everyone’s attention.

If you’re learning drum fills, this pattern should be one of the first that you try, as it’s one of the easier fills to read and play.

Example 2

In example 2, we’re taking things to the next level.

As you can see on the score above, we’re going to use 2 beats worth of semiquavers (8 in total) and we’re going to spread the fill around 4 different drums.

Because different drums have different pitches (they sound higher or lower), we can make fills that are more musical by including a variety of drums.

You might have noticed that I’m including a couple of drums that we haven’t seen yet in any examples up to this point.

We’re kicking things off with 2 snare drums and 2 bass drums, but then we’re rather cheekily sticking a snare drum, high tom, low tom and bass drum into the last beat.

Altogether, they create a fiery combination.

Example 3

Turn on hard mode, it’s time for example 3.

Have you ever heard one of those huge drum fills that you can’t help but air drum along to?

For me, it’s the famous drum fill that opens the last section of ‘In The Air Tonight’.

In songs like that, the fill becomes more than just a variation that the drummer plays.

These fills tend to be longer, and stand out from the music more.

However, you should always pick a fill that still fits with the music.

Luckily for us, sometimes that involves unveiling that huge drum fill that we’ve been practising for ages.

Here’s one I made earlier.

Writing and reading your own drum music with crotchets, quavers and semiquavers

Now you can really play drums with these three note values, mixing them all up as much as you like in the beats you create.

Just as excitingly, with these three note values under your belt, you have the power to read an incredible range of drum beats right off the page.

Take a bow, you’ve done amazingly well to get this far through the guide and we’re on the home straight.

It’ll take you some time to learn the different permutations (varieties) of these notes and how they interact with one another, but you are well on your way to a solid understanding of drum score.

If you’re unsure about any beat and how it sounds, you can always replicate it in Guitar Pro or count through it slowly.

Use the ‘1,2,3,4’ ‘1 and 2 and 3 and 4 and’ plus the ‘1 e and a 2 e and a 3 e and a 4 e and a’ that represent each of the note values we’ve discussed.

Then match up the sheet music to your counting.

Where do the notes on the page land on your counting? Can you imagine how they would sound over your counting?

The stage is yours

You now have a whole world of ideas available to you that most drummers aren’t exposed to.

There are so many great drum books out there with legendary musical ideas committed to sheet music.

There’s just one final thing you need to know before I send you out into the world as bonafide sheet music readers!

Understanding rests

If there’s one thing you probably want to do after digesting so many important concepts about sheet music, it’s to take a break.

Music also needs these periods of regular downtime and relaxation.

A rest is the opposite of a note. In short, it tells you when not to play.

In music, the rests can often become more important than the notes themselves.

Every rest makes the notes surrounding it stand out more to the listeners’ ears.

So before you launch into that fiery drum fill, be careful not to play too many notes in the build-up.

You don’t want to distract your listeners before the big finale!

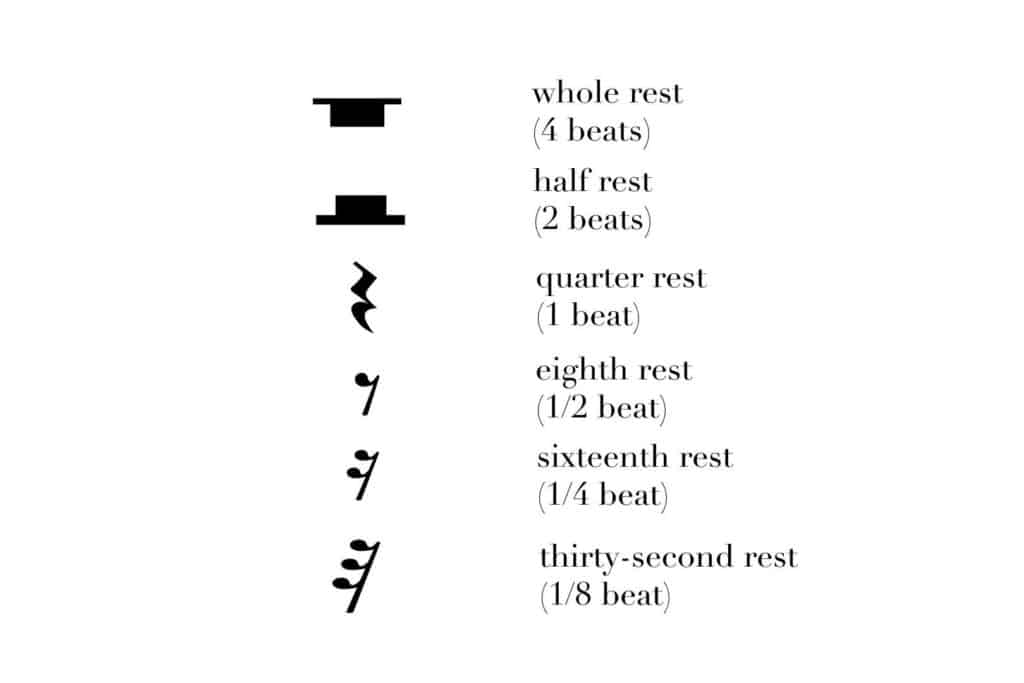

Note values of rests

The note value of a rest tells you how long that rest is for.

These rests have exactly the same names and note values as the ones we looked at earlier.

Therefore:

- A crotchet rest lasts for one beat.

- A quaver rest lasts for ½ a beat.

- A semiquaver rest lasts for a ¼ of a beat.

The major difference is that we drop all the golf clubs and go for a range of fun squiggles instead.

You can refer back to this chart anytime you need to check which rest is which.

Pretty soon, these will become second nature to you and you’ll be able to identify these on the go, whatever drum notation you happen to be reading.

The grand finale – my top tips for reading drum sheet music

Congratulations! You’ve just learnt one of the most valuable skills that a drummer could possibly have.

Give yourself a pat on the back. Go watch a movie. Put your feet up. You’ve earned it!

This will make everything so much easier on your journey to become a better drummer.

Before you go, I just thought I’d give you a rundown of top tips that will help you get the most out of reading drum notes and notation.

How’s learning sheet music for drums going for you? Let us know in the comments section below.

Getting the most out of drum notation

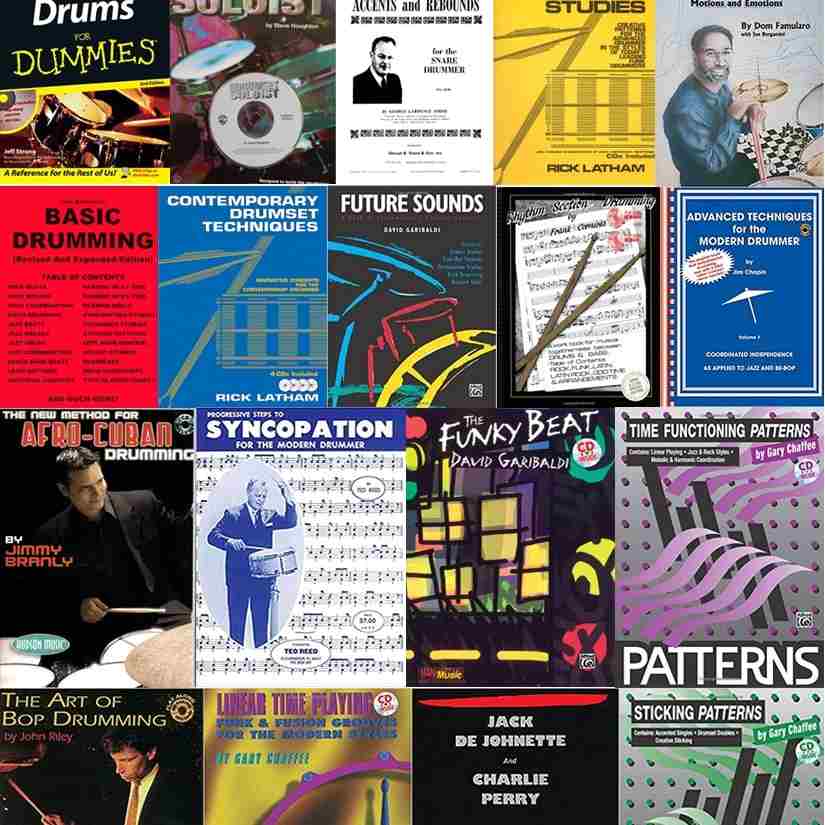

1. Learn from the experts – Now you have access to the hundreds of drum books written by world-class drummers.

They contain ideas from every style of music that you can apply to your own playing in whatever way you see fit.

There are so many to choose from, but some drum notation books that have really benefited me include:

Groove Essentials 1 and 2 by Tommy Igoe (For Beginners to Advanced)

Drum Techniques of Led Zeppelin (For rock beat lovers – Intermediate/Advanced)

The Art of Bop Drumming (For jazz lovers – Intermediate)

The links above take you to the Amazon listing for each book.

2. Drum grades – A great way of getting a drum book that is tailored exactly to your level is to get a drum grade book.

Don’t worry, it doesn’t mean you have to take an exam!

You’ll be able to pick a level of music reading that isn’t too difficult and this will keep you on track and stop you from becoming demotivated.

They each contain a number of backing tracks that you’ll be able to drum along to; this can be a really great way to have a range of tracks that you can perform for people.

With Rockschool for example, many of the backing tracks are based on real songs from famous artists.

You can find out more about them here.

It’s recommended that you take about a grade a year, so if you’ve been playing for a couple of years, you might want to have a go at grade 2.

If you’ve just started playing drums, the debut grade might be your best option.

3. Use Guitar Pro to speed up your progress – It’s so useful to have the notes on the page brought to life using software like Guitar Pro.

As long as you recognise crotchets, quavers and semiquavers, (just remember to count the decorations on the golf clubs), you’ll be able to:

- Copy beats that use those note values into Guitar Pro.

- Hear back beats from your favourite drum books.

- Create your own beats and hear how they sound on the drum kit.

Even though I read music to a professional level, I still use it as a creative tool to write down my ideas for beats and solos.

Good luck in your drum sheet music reading and most importantly, don’t forget to have fun!